May 22, 2023

•

5 min read

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Have you ever wondered who was Emiliano Zapata? At Expat Insurance, we know how difficult it can be to learn the history of Mexico and the Mexican Revolution. Click here to learn more!

Rafael Bracho

Insurance Expert

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

People of Mexican History

Introduction:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

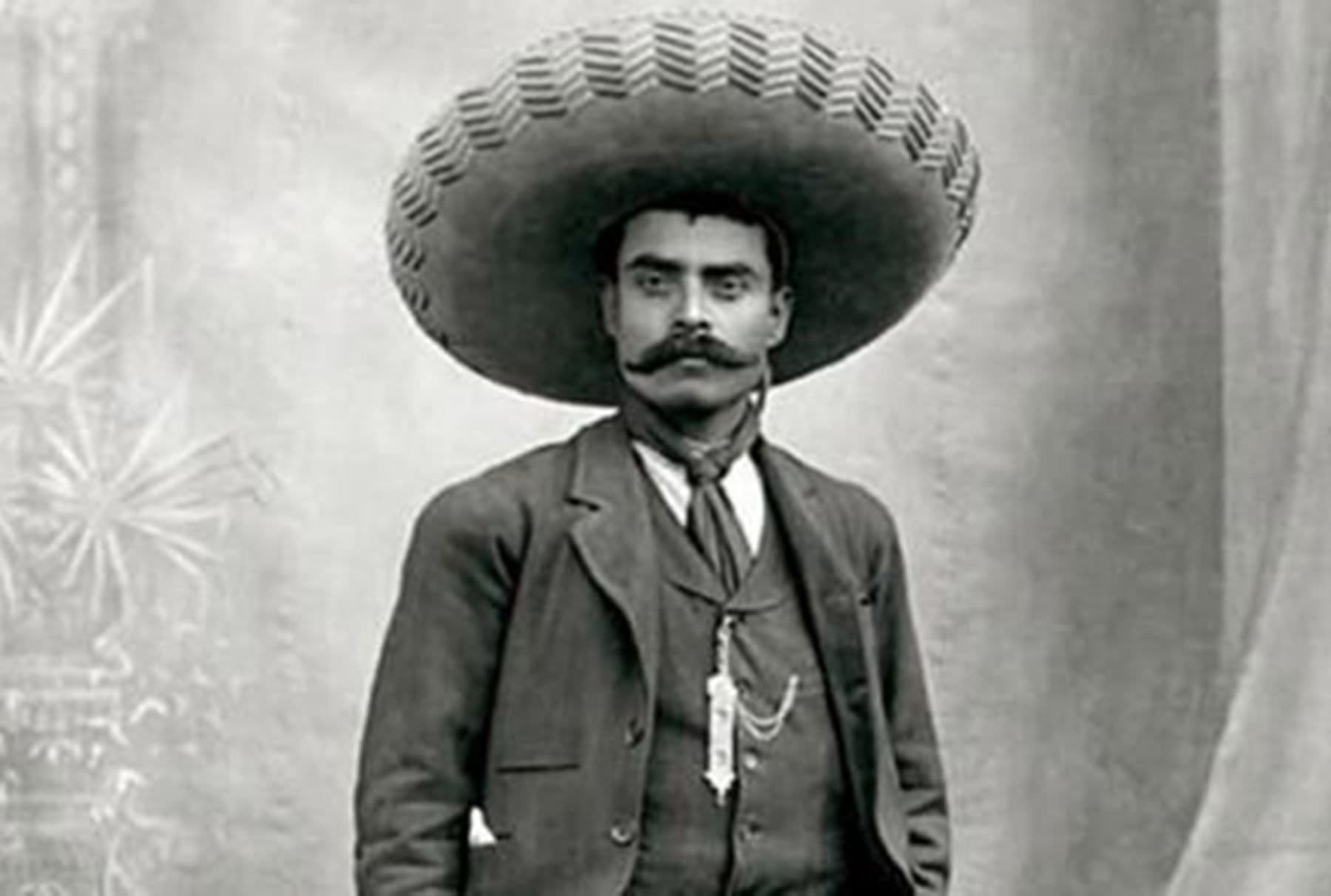

One of the most famous Mexican revolutionaries, today, Emiliano Zapata is seen by the Zapatistas as a symbol of the struggle for land and liberty of the Latin American peasantry. A staunch and uncompromising idealist, Zapata fought against social injustice—in particular, highlighting the concerns of Mexican farmers.

At Expat Insurance, we know that learning about Mexican history (and this history is still alive today) can be difficult when you didn’t grow up in Mexico. I have seen the daily toasts to Emiliano Zapata (100 years later) in the bars of Chiapas. Understanding Mexican history is part of what it means to assimilate into another culture.

Easily recognized by his sombrero and Zapatista mustache, Emiliano Zapata’s forces have become the stuff of legend in southern Mexico. As zapatismo has become ingrained as a part of the culture of southern Mexico, this revolutionary leader will live on for another hundred years.

In this article, we will give a basic overview of Zapata’s life, his rise to power, his struggle for tierra y libertad, and his death in 1919—only 39 years old.

Emiliano Zapata’s Early Life:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Emiliano Zapata was born in the pueblo of Anenecuilco in the small state of Morelos (where this article is currently being written). Born second-youngest into a family of ten, Emiliano had six sisters—and of his three brothers, one, Eufemio, would also attain the rank of general for the Revolutionary Army.

Contrary to popular opinion, the Zapata family was a middle-class family, and had a long tradition of military service. His maternal grandfather was a veteran, as were his paternal uncles. They were descended from the Zapata of Mapaztlan, and were of mestizo origin—and some eyewitness accounts claim that Emiliano was fluent in the Nahuatl language.

At the age of nine, he saw firsthand the subjugation of the peasantry as wealthy landowners expanded their haciendas and dispossessed the poor’s land. When his father said nothing could be done, young Emiliano turned to him and said, “Nothing can be done? Well, when I am grown, I’ll make them return the land.”

As a youth, Zapata received a rudimentary education from his teacher, Emilio Vara, which included the basics of bookkeeping. In addition, he learned farming and horse training from his father Gabriel—and even competed in rodeo, races, and bullfighting on horseback competitions—all of which would prove invaluable in the coming years.

At the age of 16, Emiliano’s mother died. Within the year, he would lose his father as well. An entrepreneurial youth, Zapata worked as a watermelon farmer and bought a team of mules to haul corn from local farms to the Chinameca Hacienda. Then, on June 15th, 1897, the rural forces of Cuernavaca arrested Emiliano during Anenecuilco’s town festival. His brother, Eufemio, secured his release from custody at gunpoint—and the Zapata brothers fled to the state of Puebla.

Emiliano Zapata First Days in Politics:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

In 1906, Zapata went to Cuautla to attend a meeting held by rebellious peasants on how to defend their land against neighboring landowners. This rebellious act condemned him to conscription by the Mexican army, and by 1908 he had been incorporated into the 9th Cavalry Regiment based in Cuernavaca.

There, he was assigned the job of cavalryman to Pablo Escandon, President Porfirio Diaz’s Chief of Staff. Shortly after, he was assigned the same duties for Ignacio de la Torre—who happened to be President Diaz’s son-in-law. Torre came to recognize Zapata’s skill and knowledge of horses and grew fond of young Emiliano.

Zapata was a member of the Melchor Ocampo Club—founded in early 1909 in Villa de Ayala. They were opposed to Patricio Leyva’s candidacy, seeing as how he was the establishment candidate. By September of 1909, Emiliano had already been elected calpuleque (president or chief) of the Defense Council (Junta de Defensa) of Anenecuilco, Moyotepec, and Villa de Ayala.

This position granted Emiliano Zapata access to documents originating from the viceroyalty that had been hidden from him because of Reform Laws like the Lerdo Law, which forced unproductive lands to be sold or taken over by the state. (To learn more, click here and read our article, What Is An Ejido?) He found that several hacienda owners had been bending these laws to appropriate lands and increase the size of their haciendas. This revelation, above all, would spark a fire under him and catapult Zapata as an agrarian leader in the state of Morelos.

Within 5 months, in 1910, Emiliano Zapata would be forcibly conscripted as a private into the 9th Cavalry Regiment based in Cuernavaca.

Zapata Joins the Mexican Revolution:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Many activists have their pet cause—their baby. Mine is fresh water, and for Emiliano Zapata it was land reform. So when Francisco I. Madero released his Plan de San Luis—which could be considered the Mexican Revolution’s equivalent of Martin Luther nailing the 95 theses to the Wittenberg’s Castle Church; a spark that caught the flame of revolution.

Emiliano Zapata read the Plan de San Luis. In particular, he was drawn to Article 3 which addressed land reform, offering restitution to the land owners whose lands had been stolen. An agreement was struck where Pablo Torres Burgos was sent to meet with Madero in Texas (he was the most literate of the group). The meetings were successful and on Burgos’ return, Zapata joined an army of 60 peasants who took up arms to join the Mexican Revolution.

By March 10th, 1911, Zapata had mobilized this force—which had grown to 1,000 men calling themselves the Southern Maderistas, He adopted the Plan de San Luis and he was ready to take on the Mexican government—and the government didn’t disappoint. Emiliano Zapata soon found himself pursued by Aureliano Blanquet and his battalion.

During this period, Zapata fought the battles of Chinameca, Tlayecac, Jojutla, Tlaquiltenango, Jonacatepec, and others. During this fighting, Pablo Torres Burgos would die, and Zapata was elected the leader of the Southern Maderistas on March 29th, 1911. At the heart of Zapata’s cause was agrarian reform—so much that the motto of their struggle became, “The land belongs to those who work it.” This was unacceptable to dictator Porfirio Diaz and to the hacienda owners who supported him (my direct descendants being among them).

The Plan de Ayala:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Emiliano Zapata based his headquarters in Cuautlixco—a small pueblo near Cuautla. From there he took the offensive, directing an attack on Commander Gil Villegas of the Rural Corps and Colonel Eutiquio Munguia with the entire 5th Regiment. Between April 2nd (exactly 112 years ago to the day as I’m writing this) and May 13th, 1911, Emiliano Zapata slowly took the outlying pueblos and then conquered the city of Puebla.

This series of losses forced dictator Porfirio Diaz, the establishment president of Mexico, to resign. Interim president, Francisco Leon de la Barra, took over. Again Zapata found himself defending a ferocious attack from the federal government.

The constitutionalist, Francisco I. Madero, had triumphed—in part due to Emiliano Zapata and his army. However, he wouldn’t allow his troops to be discharged without guaranteeing that each man be granted the security of land to farm in exchange for their rifle. For Zapata, the war didn’t end with the overthrow of Porfirio Diaz. It wasn’t over until the land that had been taken by the hacienda owners was returned to the peasants.

Zapata’s reluctance to put down his arms led to Francisco Leon de la Barra—the interim president after Porfirio Diaz—to declare Zapata a rebel. Leon de la Barra sent generals Aureliano Blanquet and Victoriano Huerta with a thousand men to subdue Emiliano Zapata, but they couldn’t capture him.

By August of 1911, Francisco I. Madero agreed to meet with Zapata to try and resolve the conflict in the south without more bloodshed. Unfortunately, they didn’t see eye-to-eye. Zapata firmly believed that agrarian reform was the most important point of the revolution, whereas Madero thought that sweeping political reforms had to take place first before they could take on the hacienda owners. Emiliano Zapata felt that Madero had betrayed the ideals of the Mexican Revolution.

Meanwhile, the conservative press heavily criticized Emiliano Zapata, painting him as a loose cannon and a thug. Again, the federal government sent an army after Zapata—who took a defensive strategy deploying his army—now called the Liberation Army of the South—along the border between the Mexican states of Puebla and Guerrero.

During this time, Zapata married Josefa Espejo, and, curiously, Francisco I. Madero was the best man at the wedding.

Soon after, Madero replaced the interim president, Francisco Leon de la Barra—finally taking the position of the Mexican president himself. Francisco I. Madero again met with Zapata in the National Palace. He offered Zapata a large plot of land in his home state of Morelos “as payment for his services to the revolution” if he would only lay down his arms.

Zapata declined the offer—slamming his Winchester pistol hard on Madero’s desk—and said:

No, Mr Madero. I did not rise up in arms to conquer lands and farms. I rose up in arms so that what was stolen can be returned to the people of Morelos. So then, Mr. Madero, either you fulfill what you promised us, to me and to the state of Morelos, or the Chichicuilota takes you and me. Zapata refused to become everything he had fought against: a hacienda owner who had stolen land from the peasants who farmed it. In November of 1911, Emiliano Zapata would form his own plan: the Plan of Ayala—written by Otilio E. Montaño—where its chief concern was the redistribution of the haciendas to the peasants who had worked the land. It also proclaimed that Pascual Orozco was the true leader of the revolution and deserved to be the Mexican president—not Francisco I. Madero.

It also called for a constitutional convention where all the figures of the Mexican revolution could voice their opinion. The Plan de Ayala proclaimed that so long as the peasant’s needs weren’t met, the violence would not end. Zapata famously said, “No justice for the people, then no peace for the government.” The Plan of Ayala represented the first formal document of socialist thought in Mexico. The Plan de Ayala as a document would inspire and influence other revolutionaries around the world from Russia to Cuba.

In 1912, the federal government, sent three armies against Zapata, commanded by generals Felipe Angeles, Arnoldo Casso Lopez, and Juvencio Robles. The Zapatista army fought for survival—with all the brutality that are characteristic of the worst parts of war. Beatings, fires, and rapes were common; we must be careful not to romanticize these men. Notable battles that stand out are Tepalcingo, Yautepec, Cuautla, and Cuernavaca—where this article is currently being written.

It’s wise to note that at this time that Emiliano Zapata’s political influence and militaristic might was fairly weak. El zapatismo could have disappeared if those early campaigns had succeeded in crushing the Zapatista army.

Zapata’s Rise in Influence:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

On February 22, 1913, Madero was assassinated—ordered by Victoriano Huerta. Venustiano Carranza was named as the new president. However, Huerta held the true power.

During this period, Zapata’s influence grew as well, which drew men to his army. Soon, Emiliano Zapata was one of the most important revolutionary figures. He began implementing his land reform policies in the small state of Morelos.

Zapata now controlled the states of Puebla, Guerrero, Tlaxcala, Morelos, and part of the State of Mexico—he was a real threat to the establishment.

Victoriano Huerta sent an envoy led by Pascual Orozco’s father (also named Pascual Orozco) who Zapata had declared in the Plan de Ayala as the true leader of the revolution. On their arrival, they sent a messenger to arrange a meeting. Emiliano Zapata shot the messenger saying he refused to make peace with the men who had murdered Francisco I. Madero. It seems, for all their differences, Zapata cared deeply for Madero—the man who’d been the best man at his wedding.

In May of 1913, after the confrontation with Huerta’s delegation, Emiliano Zapata edited his Plan de Ayala document, denouncing Victoriano Huerta, as well as Pascual Orozco, leaving Zapata himself as the sole commander of the Liberation Army of the South—which now numbered 27,000 men.

Zapata continued his military campaign, taking Jonacatepec, Chilpancingo, Cuajimalpa, Xochimilco, and Milpa Alta. The Zapatistas were now a direct threat to Mexico City. As the Liberation Army of the South approached the capital, the citizens fled in fear. Huerta’s constitutionalist forces occupied the city, while Zapata’s forces laid siege.

Venustiano Carranza tried to arrange another parley, but Zapata rejected the request for a meeting. Zapata demanded that Carranza resign as president and the Plan of Ayala be adopted by the standing government.

Venustiano Carranza was more of a moderate constitutionalist. He believed the plan was too radical for Mexico at the time.

The Conventionist Government:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

In September of 1914, using his base of operations in Cuernavaca as a temporary capital for his ad hoc government, Emiliano Zapata began relegating the land under his control to the towns themselves.

A meeting was organized, the Aguascalientes Convention, where all the top revolutionaries were invited to discuss the future of Mexico, to try and settle their differences, draft a new constitution, and create a stable government. Zapata didn’t attend the meeting himself, but he sent trusted associates to represent him as delegates at the convention.

The Aguascalientes Convention chose not to invite Venustiano Carranza.

One prominent general who did attend the convention was Pancho Villa. The Zapatista delegation got along well with Pancho Villa’s ideals, and Zapata’s forces joined Villa’s. They named Eulalio Gutierrez as their provisional Mexican president—and together they denounced Carranza’s government. In November of 1914, Villa’s Northern Division and Zapata’s Liberation Army of the South conquered Mexico City. This catapulted Zapata to international fame.

(Click here to read our article on Pancho Villa.)

On December 4th, Zapata and Villa met in person in Xochimilco. Pancho Villa adopted the Plan de Ayala—except for the part of the document that denounced Francisco I. Madero—whom Villa had supported.

Zapata retook Puebla on December 17th, 1914. He wouldn’t hold it for long however, because by January he’d lost the city to General Álvaro Obregón—who was loyal to Carranza’s government. This occupied Zapata’s army, in effect leaving the state of Morelos to be governed by the peasants inhabiting the area.

Villa’s army suffered major defeats at the hands of Álvaro Obregón—in a large part because of the pioneering use of aviation in warfare. First the constitutionalists took Mexico City; and then Cuernavaca.

For the next couple years, Emiliano Zapata would struggle to retake his home state of Morelos against the forces of General Pablo González, though by 1918, he was facing an uphill battle, waging a guerilla war and running out of supplies.

To make matters worse, Carranza passed a law designed to appease the peasant leaders without enacting real, substantial change.

Emiliano Zapata’s Death:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

In April of 1919, Colonel Jesús Guajardo sent a message to Emiliano Zapata, saying that he’d become disillusioned with Carranza’s government. Jesús Guajardo told Zapata that he wanted to join Zapata’s forces fighting their guerilla war.

Fearing a trap, Zapata asked Colonel Jesús Guajardo to prove his commitment to the revolutionary cause. In response, Guajardo shot fifty federal soldiers (secretly with the consent of Pablo González and Venustiano Carranza).

After this show of loyalty, Zapata agreed to meet Jesús Guajardo in Chinameca, Morelos on April 10th, 1919.

On arrival, he approached the hacienda and a soldier began playing the call to honors on his bugle. This was the signal for Guajardo’s men to open fire from the rooftops.

A bullet took him in the chest, and Emiliano Zapata died on impact. Then, the constitutionalist soldiers proceeded to shoot Zapata’s corpse in the chest over twenty times with a shotgun. A photo was taken shortly after, which became a symbol that spread throughout all of Mexico. His murder was widely condemned.

Zapata’s Legacy:

Who Was Emiliano Zapata?

Though Zapata’s movement fizzled out shortly after his death, his legacy lives on. Zapatistas continue to fight for agrarian reform and the betterment of the lives of the peasants in Mexico. Most notably, in 1994, Zapatistas took control of San Cristobal de las Casas, forcing the government to concede to reforms.

Zapata lives on, not only as a famous figure in the Mexican Revolution, but also as a peasant leader who fought against injustices and for the rights of the poor farmers who worked the land. He may have been ruthless, a man who lived in violence until his dying day—never wavering from his cause and his personal code of honor.

Rafael Bracho

Insurance Expert & Writer

For several years, Rafael has been crafting articles to help expats and nomads in their journey abroad.

Get Protected While Living Abroad

Found this article helpful? Make sure you have the right insurance coverage too. Get instant quotes for international health, life, and travel insurance.

Takes 2 minutes • Compare multiple providers • Expert advice